Als New Scientist het IPCC om opheldering begint te vragen, zoals in de editie van afgelopen week gebeurde (zie ook de afbeelding hierboven), dan weet je dat er wel iets bijzonders aan de hand moet zijn. New Scientist gaat namelijk al jaren voorop in de strijd om meer aandacht voor klimaatverandering en zal zelden tot nooit een sceptisch geluid laten horen. Geregeld plaatst het Engelse populairwetenschappelijke weekblad (dat ik persoonlijk zeer lezenswaardig vind over de meeste onderwerpen en geregeld gebruik om me in te lezen bij nieuwe onderwerpen waarover ik moet schrijven, alleen hun stukken over klimaat zijn zeer alarmistisch en eenzijdig) zelfs stukken die de argumenten van sceptici weerleggen, zoals hier in 2007. David Pearce, de klimaatjournalist van New Scientist, schreef enkele boeken over klimaat waaronder De laatste generatie, hoe de natuur wraak neemt, dat door Maurits Groen en Jan van Arkel voor slechts 5 euro op de markt werd gebracht in Nederland om ons te bekeren. De titel geeft aan waar het heen gaat, Pearce geeft een selectie van in potentie alarmerende ontwikkelingen in het klimaat, zoals het vrijkomen van methaan uit de permafrost en het stilvallen van de golfstroom.

Dus wat moet er in godsnaam aan de hand zijn als deze verkondiger van het evangelie hun eigen hogepriester, het IPCC, ter verantwoording begint te beroepen. Voor de duidelijkheid hier nogmaals de tekst uit het bovenstaande plaatje:

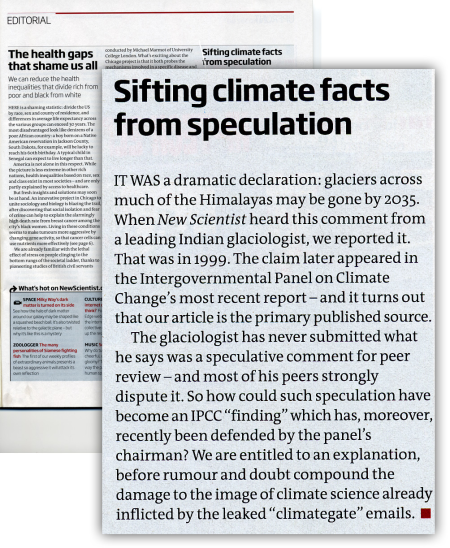

IT WAS a dramatic declaration: glaciers across much of the Himalayas may be gone by 2035. When New Scientist heard this comment from a leading Indian glaciologist, we reported it. That was in 1999. The claim later appeared in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s most recent report – and it turns out that our article is the primary published source.

The glaciologist has never submitted what he says was a speculative comment for peer review – and most of his peers strongly dispute it. So how could such speculation have become an IPCC “finding” which has, moreover, recently been defended by the panel’s chairman? We are entitled to an explanation, before rumour and doubt compound the damage to the image of climate science already inflicted by the leaked “climategate” emails.

New Scientist wil graag weten van het IPCC hoe het mogelijk is dat een uitspraak van de Indiase onderzoeker Syed Hasnain in 1999 in New Scientist een algemeen aanvaard feit is geworden in de klimaatwereld en ver daarbuiten, omdat het IPCC deze uitspraak als basis heeft gebruikt in het vierde IPCC-rapport in 2007 om te beweren dat de gletsjers in de Himalaya in 2035 verdwenen zullen zijn. Je zou er als blad ook trots op kunnen zijn dat je invloed zo ver reikt, dat je zo gezaghebbend bent dat zelfs het IPCC alles wat er in je blad staat klakkeloos overneemt, maar ook New Scientist realiseert zich dat het zo toch niet zou moeten werken. Ook New Scientist gaat ervan uit dat het IPCC zich baseert op de altijd als hoogste graad van betrouwbaarheid geldende peer review literatuur.

Grondigste peer review

Want het IPCC beweert zelf de grondigste peer review denkbaar te hanteren. Dit zei Sir John Houghton, de toenmalige vice-voorzitter in 2001 bij de presentatie van het derde rapport over de peer review van het IPCC:

“It had been reviewed by governments before we came here, and in fact it’s probably one of the most peer-reviewed documents you could ever find.”

De huidige voorzitter van het IPCC, Rajendra Pachauri, zei tijdens zijn openingsrede van de klimaatconferentie in Kopenhagen nog het volgende:

The IPCC assessment process is designed to ensure consideration of all relevant scientific information from established journals with robust peer review processes, or from other sources which have undergone robust and independent peer review. The entire report writing process of the IPCC is subjected to extensive and repeated review by experts as well as by governments. In the AR4 there were a total of around 2500 expert reviewers performing this review process.

Vorige week nog, in het spoeddebat in de Tweede Kamer over climategate benadrukte minister Cramer van VROM nog dat ze zich baseert op het IPCC omdat het om zo’n grote groep wetenschappers gaat en dat er in de wetenschappelijke wereld een ‘zeer gedegen peerreviewsysteem’ gehanteerd wordt:

Zoals ik al zei, is het mijn uitgangspunt dat niemand wordt uitgesloten. In de rapporten van het IPCC worden de klimaatsceptici vermeld. Hun informatie wordt meegenomen. De wetenschappelijke wereld kent een zeer gestructureerd proces van hoor en wederhoor. Datgene wat men aan wetenschappelijk onderzoek rapporteert, moet met feiten gestaafd worden. Dat is een zeer gedegen peerreviewsysteem. Mensen houden elkaar voortdurend bij de les over wat waar is en wat niet. Politici moeten zich baseren op de uitkomsten van zo’n heel grote groep wetenschappers. Het gaat om 1200 instituten met tig duizend mensen. Zij creëren met al die gegevens een beeld voor ons dat wij gebruiken als uitgangspunt.

Welnu, in december was het al duidelijk geworden dat een stevige bewering uit het vierde IPCC-rapport, namelijk dat de gletsjers in de Himalaya in 2035 verdwenen zouden zijn als de opwarming van de aarde zich in het huidige tempo zou voortzetten, waarschijnlijk te herleiden was tot een typefoutje. Dat New Scientist daarbij een rol had gespeeld werd toen ook al duidelijk. We berichtten daar op 23 december ook hier over, maar het is goed om even een korte samenvatting te geven voordat we verder gaan met nieuwe uitspraken van betrokkenen in New Scientist over dit onderwerp.

Geen typefout

De Amerikaanse klimaatonderzoeker John Nielsen-Gammon (die zich zelf niet direct met gletsjers bezig houdt) ging in december aan de slag met een blogbericht van Madhav Kandhekar, een in Canada wonende en gepensioneerde (sceptische) klimaatonderzoeker. Hij en ook Khandekar baseerden zich op informatie van de Canadese fysisch geograaf Graham Cogley. Nielsen-Gammon schrijft er op 22 december een uitgebreid blogbericht over, dat wij gebruikten als aanleiding voor ons bericht. Eerst de gewraakte passage uit het vierde IPCC-rapport:

“Glaciers in the Himalaya are receding faster than in any other part of the world (see Table 10.9) and, if the present rate continues, the likelihood of them disappearing by the year 2035 and perhaps sooner is very high if the Earth keeps warming at the current rate. Its total area will likely shrink from the present 500,000 to 100,000 km2 by the year 2035 (WWF, 2005).” (IPCC AR4 WG2 Ch10, p. 493)

In zijn blogbericht maakt Nielsen-Gammon aannemelijk dat de fout in het IPCC-rapport waarschijnlijk geen typefout is – 2035 i.p.v. 2350 zoals Khandekar en Cogley op dat moment beweerden – maar dat 2035 afkomstig is van New Scientist.

Both Khandekar and Cogley seem to blame the error on a misreading by the IPCC authors, but I think this is incorrect. The truth is quite a bit more interesting, and the evidence is in the written documents. Let’s have a look.

The IPCC report lists a single reference for the paragraph: WWF 2005. This turns out to be a World Wildlife Fund project report (PDF) that was not peer-reviewed. This is a problem; the IPCC is supposed to rely only on the peer-reviewed literature.

Dan volgt het relevante citaat uit het WWF-rapport. Maar dan vervolgt Nielsen-Gammon:

This is another problem: the WWF report is only quoting another source, so not only is it not peer-reviewed, it is a secondary source. This leads to the danger that the WWF has not quoted the primary sources completely correctly. (…) The primary sources are stated to be a 1999 report by WGHG/ICSI and what turns out to be a 1999 article in New Scientist magazine. The latter source wouldn’t even be acceptable as a primary source, but let’s see what it says:

“A new study, due to be presented in July to the International Commission on Snow and Ice (ICSI), predicts that most of the glaciers in the region will vanish within 40 years as a result of global warming. “All the glaciers in the middle Himalayas are retreating,” says Syed Hasnain of Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, the chief author of the ICSI report….Hasnain’s four-year study indicates that all the glaciers in the central and eastern Himalayas could disappear by 2035 at their present rate of decline….Hasnain’s working group on Himalayan glaciology, set up by the ICSI, has found that glaciers are receding faster in the Himalayas than anywhere else on Earth. Hasnain warns that as the glaciers disappear, the flow of these rivers will become less reliable and eventually diminish, resulting in widespread water shortages.”

Moddergevecht

Het was Fred Pearce die Hasnain in 1999 interviewde in New Scientist en zoals gezegd is hij nog steeds de klimaatredaceur van het blad. Het was dus logisch dat Pearce Hasnain om een reactie zou vragen, maar ook de lead author van het betreffende IPCC-hoofdstuk, de Indiase glacioloog Murari Lal. Dat levert op 11 januari van dit jaar een moddergevecht op in New Scientist.

Glaciologists are this week arguing over how a highly contentious claim about the speed at which glaciers are melting came to be included in the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

In 1999 New Scientist reported a comment by the leading Indian glaciologist Syed Hasnain, who said in an email interview with this author that all the glaciers in the central and eastern Himalayas could disappear by 2035.

Hasnain, of Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, who was then chairman of the International Commission on Snow and Ice’s working group on Himalayan glaciology, has never repeated the prediction in a peer-reviewed journal. He now says the comment was “speculative”.

Despite the 10-year-old New Scientist report being the only source, the claim found its way into the IPCC fourth assessment report published in 2007. Moreover the claim was extrapolated to include all glaciers in the Himalayas.

Oeps, dit is vast iets waar minister Cramer niet zo blij mee is. Stel dat een citaat van een scepticus tot absolute waarheid verheven zou worden in het IPCC-rapport. Ondenkbaar. Maar het tegenovergestelde, een opmerking van een alarmist in de media, kan dus wel zomaar de eindstreep halen. Ondanks het zeer gedegen, robuuste peerreviewsysteem.

Als door een wesp gestoken

Het wordt extra pikant omdat een Indiaas rapport in november nog stelde dat het met het terugtrekken van de gletsjers in de Himalaya best mee lijkt te vallen. Pachauri reageerde toen meteen als door een wesp gestoken.

In de Guardian zei Pachauri:

“Pachauri dismissed the report saying it was not “peer reviewed” and had few “scientific citations”.

“With the greatest of respect this guy retired years ago and I find it totally baffling that he comes out and throws out everything that has been established years ago.”

En nu in New Scientist:

Chapter 10 of the [IPCC] report says: “Glaciers in the Himalaya are receding faster than in any other part of the world.”

The inclusion of this statement has angered many glaciologists, who regard it as unjustified. Vijay Raina, a leading Indian glaciologist, wrote in a discussion paper published by the Indian government in November that there is no sign of “abnormal” retreat in Himalayan glaciers. India’s environment minister, Jairam Ramesh, accused the IPCC of being “alarmist”.

The IPCC’s chairman, Rajendra Pachauri, has hit back, denouncing the Indian government report as “voodoo science” lacking peer review. He adds that “we have a very clear idea of what is happening” in the Himalayas.

Aangedikt

Pachauri beweert dus een duidelijk beeld te hebben van wat er gaande is in het Himalaya-gebergte, maar realiseert zich dan nog niet dat hij zich daarbij voornamelijk baseert op een tien jaar oud citaat in New Scientist. Pearce meldt tevens dat IPCC het WWF-rapport (dat zich dus baseerde op New Scientist 1999) nog even heeft aangedikt:

Nonetheless, the IPCC report goes further, concluding without citing further evidence that the prediction is “very likely” – a term that it says means a likelihood of greater than 90 per cent.

Graham Cogley, a geographer from Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, says the 2035 date is extremely unlikely. “At current melting rates it might take up to 10 times longer,” he says.

Hoe reageert het IPCC nu op deze onthullingen. De beurt is aan Murari Lal, lead author van het betreffende hoofdstuk in het WG2 IPCC-rapport. Maar in de inmiddels bijna bekende het IPCC-heeft-lak-aan-alles-stijl veegt Lal alle beschuldigingen van fouten van tafel:

However, the lead author of the IPCC chapter, Indian glaciologist Murari Lal, told New Scientist he “outright rejected” the notion that the IPCC was off the mark on Himalayan glaciers. “The IPCC authors did exactly what was expected from them,” he says. “We relied rather heavily on grey [not peer-reviewed] literature, including the WWF report,” Lal says. “The error, if any, lies with Dr Hasnain’s assertion and not with the IPCC authors.”

Logica

Alle logica is zoek in deze reactie, want stel dat we ‘m accepteren, dan betekent het dat de peer review van IPCC dus niets voorstelt. Want IPCC accepteert blijkbaar blindelings nogal stevige beweringen uit grey literature. Ook Lal kunnen we dus een verwijzing sturen naar deze website, waar kant-en-klare tips staan wat je moet doen in tijden van crisis. We schreven daar eerder hier over. Zo schrijven de deskundigen op het gebied van crisiscommunicatie:

Weet dat alles uiteindelijk toch uitkomt. Kom dus meteen naar buiten met negatieve informatie. Hoe minder informatie de media en het publiek krijgen, hoe groter de kans op speculatie. Bepaal ook zelf het kader van de discussie. Stem je communicatie bijvoorbeeld niet af op een aanval.

Hasnain kan dan ook terecht niet leven met de kritiek van Lal:

But Hasnain rejects that. He blames the IPCC for misusing a remark he made to a journalist. “The magic number of 2035 has not [been] mentioned in any research papers written by me, as no peer-reviewed journal will accept speculative figures,” he told New Scientist.

“It is not proper for IPCC to include references from popular magazines or newspapers,” Hasnain adds.

Ha, dat is interessant, een peer-reviewed journal zou zoiets volgens Hasnain dus nooit accepteren, maar het IPCC blijkbaar wel. Hasnain komt er zelf overigens wel wat gemakkelijk vanaf in New Scientist. Want je neemt toch aan dat hij als Indiase glacioloog weet dat het IPCC claimt dat in 2035 de gletsjer weg zijn in de Himalaya. Heeft hij zich zelf wel eens afgevraagd waarop het IPCC zich baseerde? Had hij niet wat eerder aan de bel moeten trekken? Wat weerhield hem eventueel? Op deze vragen zullen we in de nabije toekomst ongetwijfeld nog terugkomen.

Fouten erkennen

Fouten maken kan – hoe erg ook – gebeuren, zeker bij IPCC-rapporten die duizenden pagina’s dik zijn. Bij de fout die hier gemaakt is ligt de wenselijkheid van de fout er wel erg dik bovenop. Het ergste blijft echter de houding van IPCC, die altijd onmiddellijk in de tegenaanval gaat en tot op heden nooit openlijk fouten heeft erkend. Met die houding kwamen ze lange tijd gemakkelijk weg, maar na climategate lijkt zelfs de volgzaamheid van een hondstrouw blad als New Scientist te breken. Hoog tijd dus dat een spindoctor bij het IPCC zich dit ook gaat realiseren.

Dit is ook min of meer de conclusie die Roger Pielke jr, bepaald geen klimaatscepticus, maar wel steeds sceptischer over IPCC, trekt op zijn blog, hier en hier:

I discussed this situation last month in a post in which I argued that the problem here is not that the IPCC made a mistake. That is just troubling. The greater problem is how the IPCC has responded to having a mistake pointed out:

In the case of melting glaciers in the Himalayas, the IPCC 2035 claim has led to, in Nielsen-Gammen’s words, an egregious mistake becoming “effectively common knowledge that the glaciers were going to vanish by 2035.” Like the common (but wrong) knowledge on disasters and climate change that originated in the grey literature and was subsequently misrepresented by the IPCC, on the melting of Himalayan glaciers the IPCC has dramatically misled policy makers and the public.That the IPCC has made some important mistakes is very troubling, but perhaps understandable given the magnitude of the effort. Its reluctance to deal with obvious errors is an even greater problem reflecting poorly on an institution that has become too insular and politicized.

Unfortunately, the glacier error is not unique. The IPCC contains a number of other egregious errors that also deserve some answers.

Haha, geweldig! Ik weet nu al de volgende reactie van het IPCC:

"Naar aanleiding van niet-smeltende-Himalaya-gletsjersgate hebben we ons peer-reviewproces nog verder aangescherpt."

@ T2000

Heb jij thuis een glazen bol? Met de laatste reactie van het IPCC zit je toch wel erg dicht tegen de 'waarheid' :-)

Ik houd mezelf voorbehouden op nog meer voorspellingen!

Goed stuk.

Hm, je kunt natuurlijk wel eindeloos door blijven mekkeren over de fouten in het IPCC proces.

Maar intussen laten de metingen zien dat de gestage smelt van gletsjers en ijskappen rustig doorgaat. Zie bv de NSIDC metingen: http://nsidc.org/glims/glaciermelt/index.html

maar dat ontkennen jullie natuurlijk ook niet expliciet…

En ondertussen gaan allemaal warhoofden (zoals T2000) er met het verhaal vandoor: "…niet smeltende himalaya-gletsjers…"

maar dat is natuurlijk niet jullie verantwoordelijkheid…

@Boog: Het is maar wat je mekkeren noemt.

Maar ik begin wel te begrijpen waarom de alarmisten verklaren dat de woestijnen groter worden: Anders zijn ze bang dat er niet genoeg zand is om hun kop in te steken.

"…de alarmisten verklaren dat de woestijnen groter worden…"

Lees wat ik schrijf.

Het gaat er niet om of er wordt 'verklaard' dat de woestijnen groter worden of de gletsjers kleiner.

Het gaat erom dat er wordt gemeten wat er veranderd. En zoals ik liet zien laten die metingen zien dat het ijsvolume afneemt…

Leek me wel een relevante constatering op een blog wat pretendeerd 'de feiten' in het 'klimaatsdebat' weer te geven.

@boog

Waar het in dit verband om gaat is dat uit 'AGW hoek' verhalen zoals deze de wereld ingeslingerd worden die op niets gebaseerd zijn en dan tot op het bot worden uitgemolken alsof het de absolute en enige denkbare waarheid (tevens doemscenario) is.

Vervolgens wordt eenieder die waagt kanttekeningen te plaatsen bij De Waarheid, zoals bij meerderheid van stemmen door de leading scientists bepaald, tot aan zijn veters afgebrand. Niet echt wetenschappelijk toch?

En tot slot: als dan uiteindelijk blijkt dat De Waarheid niet helemaal werkelijkheid is, dan is volgens die scientists slechts sprake van een storm in een glas water, een kleinigheid, niets om je druk over te maken.

Zie je het patroon? Ben geen klimatoloog maar ik geloof mensen die iets al te zeker weten en geen tegenspraak kunnen velen nooit op hun woorden.

Kijk, dat "2035" had inderdaad nooit in het IPCC rapport opgenomen mogen worden. Maar het is net zo als met de hockeystick: de conclusie dat de gletsjers wereldwijd netto smelten is *niet* afhankelijk van de 2035-claim en wordt netjes door meetgegevens ondersteund.

Maar die gletjers smelten en groeien al miljarden jaren. Ook dat wordt door meetgegevens ondersteund.

Daar had de natuur blijkbaar geen mens voor nodig, waarom nu dan opeens wél?

Omdat het smelten samenhangt met de opwarming, en die is hoogstwaarschijnlijk het resultaat van menselijk handelen. Daarom.

(en dat er al miljaren jaren sprake is van afwisselend opwarming en afkoeling doet daar niets aan af)

De gletsjers smelten wereldwijd vanaf ongeveer 1850, de Kleine IJstijd voorbij (… gelukkig). Het woestijngebied rond de evenaar (Afrika) krimpt de laatst 20 jaar (verassend).

Prima samenvatting Marcel, chapeau!

@harold

Tja, die idioten ook bij NASA he, wat snappen zij er nou van. Dat smelten heeft niks met ons te maken! Tis gewoon een interglaciaaltje! Ruis.

En die verzurende oceanen is ook een meetfoutje natuurlijk. Heeft allemaal niks met CO2 te maken. CO2 gestegen, zeg je. Oh niks aan de hand. CO2 is goed voor planten he… enne…blablablabla.

Remco, een afname in de gletsjers vanaf 1850 verzwakt volgens mij een CO2 hypothese. Er zijn mensen die beweren dat de Kleine IJstijd verkort werd door de toename van Koolstofdioxide, het effect zou volgens mij pas veel later dan 1900 te zien moeten zijn.

Verzurende Oceanen? Vertel!

Die .7 graden Celsius stijging is trouwens volgens mij hoofdzakelijk een stijging van de nachttemperaturen.

Waarom neemt het woestijngebied in Centraal Afrika af?

De mensen die rijker van deze maatregelen worden zijn niet de armen van deze wereld.

Op RealClimate komen ze met een aannemelijke verklaring waarom deze fout door het peer-review systeem is geglipt:

"This might be related to the fact that this text was in the Working Group 2 report on impacts, which does not get the same amount of attention from the physical science community than does the higher profile WG 1 report (which is what people associated with RC generally look at). In WG1, the statements about continued glacier retreat are much more general and the rules on citation of non-peer reviewed literature was much more closely adhered to. However, in general, the science of climate impacts is less clear than the physical basis for climate change, and the literature is thinner, so there is necessarily more ambiguity in WG 2 statements."

zie http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/201…

@Boog & Remco.

Dus volgens jullie is de mens machtiger dan de natuur en kan de natuur gestuurd worden?

Uiteraard.

Hoe dacht je dan dat het komt dat Holland onder zeeniveau ligt, om maar even een ander voorbeeld dicht bij huis te zoeken?

En definieer "de natuur" eens. Een beek omleggen is óók de natuur sturen, en dat is geen enkel probleem. De draairichting van de aarde veranderen ligt daarentegen weer buiten bereik…

@leo

Nou, ik kan je wel verklappen dat de A van AGW staat voor Anthropogenic.

Grinnn, na deze antwoorden moest ik toch echt even naar mijn vraag kijken hoor. Was die nou zo onduidelijk of..?

Voor de 1 lijkt de natuur niet verder te gaan dan het klimaat met zijn wetenschap die nog aan de tiet ligt, en voor de ander ligt het het bewijs van de almachtige mens in een paar dijken?

Wetenschap is nog nooit beter geweest dan zijn eerste weerlegde conclusie, en met die dijken had de natuur in 1952 ook weinig problemen.

Remco, hoe veel duizenden weerlegde wetenschappelijke rapporten moet je nog hebben voordat je niet meer in de onfeilbaarheid van wetenschappers gelooft? Denk je écht dat men in de klimaatwetenschap alles weet over bv de werking van de oceanen, de invloed van de zon, kosmische straling en hoe de natuur op aarde daar op reageert?

Boog, misschien moet je maar eens écht natuurgeweld meemaken. Dus geen weggewaaid dakpannetje en een ontworteld boompje in de stad, maar een -niet voorspelde- orkaan midden op de Noord-Atlantic. Ik garandeer dat je in 1 klap je vertrouwen in de wetenschap verliest én dat je voor altijd weet dat de mens met al zijn technieken helemaal niets voorstelt voor moeder natuur.

Dat machtsgevoel verdwijnt dan met de spreekwoordelijke dunne st**nt die door je broekspijpen loopt.

Natuurlijk mag je nu denken "weer zo'n sterk zeemansverhaal", maar zo'n klapje wind heeft mij doen inzien dat de mens helemaal niets in de melk heeft te brokkelen wanneer de natuur even met zijn staart kwispelt.

Ten slotte nog een vraag aan jullie beiden, en deze keer zal ik proberen om duidelijk te zijn.. ;~)

Hebben jullie er een probleem mee wanneer het hele alarmistische verhaal een hoax blijkt te zijn?

Wat er impliciet ook nog meespeelt is natuurlijk het verhaal van Al Gore dat het verdwijnen van de Himalayagletsjers drinkwatertekorten in China en India zou veroorzaken.

Dat is niet zo.

De bijdrage van gletsjersmelt is verwaarloosbaar op de hydrologie. In tegenstelling tot Europa is de waterpiek in Centaal Azie in de zomer, voornamelijk veroorzaakt door regenval op 3000 m.

http://www.vkblog.nl/bericht/293177/Himalaya%3A_G…

"Wetenschap is nog nooit beter geweest dan zijn eerste weerlegde conclusie"

Zo werkt dat niet. In de aardwetenschappen is elke hypothese weerlegbaar, aangezien elke plaats en tijd uniek is. Het Popperiaanse model is dus niet bruikbaar. Waar het om gaat is welke consistente theorie het beste de observaties kan verklaren. En dan heeft de AGW hypothese gewoonweg betere papieren dan alternatieve verklaringen zoals zon, cosmische stralen of natuurlijke variabiliteit. Lees eens een attributiestudie, zou ik zeggen.

"hoe veel duizenden weerlegde wetenschappelijke rapporten moet je nog hebben voordat je niet meer in de onfeilbaarheid van wetenschappers gelooft?"

Wie heeft beweert dat wetenschappers onfeilbaar zijn? De wetenschappers zelf in ieder geval niet. Zodra er een betere verklaring voor observaties beschikbaar komt, wordt die gebruikt. Maar zoals gezegd: met Popperiaanse falsificaties heeft dat weinig van doen.

"de mens helemaal niets in de melk heeft te brokkelen wanneer de natuur even met zijn staart kwispelt."

Dat een individu het aflegt tegen een weersfenomeen is geen argument waarmee je ontkracht dat de mensheid invloed kan hebben op het klimaat.

Boog,

Interessant, ben het met je opmerking over Popper wel eens, falsificatie is heel lastig in klimaatonderzoek. Toch moeten we oppassen dat we daardoor niet alles als bewijs voor AGW gaan zien. Tien jaar geen opwarming? Geen falsificatie! Antarctica warmt niet op? Geen falsificatie! Geen hot spot in de tropen op 10 km hoogte? Geen falsificatie! Het is niet vreemd dat dit soort voorbeelden veel mensen aan het denken zet en sceptischer maakt. Voor jou kan AGW de beste verklaring zijn vor alle puzzelstukjes, maar voor diverse andere wetenschappers is het dat niet, denk aan de drie hypotheses van Pielke sr.

Over attributie gesproken, erken jij dat 'het bewijs' voor AGW is dat modellen alleen overeenkomen met observaties van de mondiale T als de broeikasgassen flink bijdragen aan de opwarming? Want volgens mij is dat nog altijd het bewijs waar het IPCC op leunt (zie ook Nature van deze week, verschijnt morgen een interessant news feature). In dat geval hangt het bewijs dus van twee belangrijke pijlers af, hoe goed zijn de modellen en hoe goed zijn de observaties? Zoals je weet valt er op beide nog heel veel af te dingen. De global T van CRU, GISS en NCDC is echt een puinhoop en als daar echt een keer goed naar gekeken wordt door 'onafhankelijke onderzoekers' (dus niet Jones en Hansen, Karl etc.) dan zal blijken dat het merendeel van de trend 'adjustment' is. Hoeveel van de trend dan UHI is, is de volgende prangende vraag. Daarna gaan we kijken naar de haken en ogen in de modellen die nog huge zijn, denk aan convectie, wolkenvorming, neerslag etc. De volgende kwestie wordt dan of de modellen al de toekomst kunnen gaan voorspellen. Lucia op The Blackboard heeft laten zien dat de voorspelling sinds 2001 voorlopig helemaal mis gaat. Ok, misschien nog te kort om de modellen helemaal af te branden, maar laten we onze ogen er ook niet voor sluiten.

"Hebben jullie er een probleem mee wanneer het hele alarmistische verhaal een hoax blijkt te zijn?"

Ik heb geen idee welk alarmistische verhaal je bedoelt.

Ik kijk naar de observaties en ik zie de klimaatontwikkeling gedurende de 20e/21e eeuw.

Ik lees de primaire wetenschappelijke literatuur, en constateer dat de AGW hypothese de beste verklaring vormt voor deze observaties.

En dat allemaal zonder hockeystick, zonder gletsjers, zonder IPCC. Heb je niet nodig ter onderbouwing van de AGW hypothese.

…en zonder Al Gore. Heb je ook niet nodig ter onderbouwing van AGW.

@Hans Errren.

Het gaat niet om de bijdrage van de gletsjers tijdens het hoogwaterseizoen, maar tijdens het droge seizoen. Dan zou smeltwater cruciaal kunnen zijn voor de waterhuishouding.

Ik heb het EGU abstract van Armstrong et al er eens op nagelezen: http://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU2009/EG… en constateer dat zij daar GEEN uitspraken over doen. Ze zeggen alleen iets over de bijdrage aan de JAARLIJKSE afvoer, maar zoals gezegd is dat minder relevant.

"The Hot" is in april, dan ligt er nog sneeuw op de bergen. Gletsjersmelt is verwaarloosbaar in de hydrologie, zelfs als de gletsjers verdwenen zijn, is er nog steeds sneeuw in de winter, de bergen zijn hoog genoeg, het zijn de hoogste bergen van de wereld.

@boog

Dank voor het beantwoorden van de vraag over de onfeilbaarheid van wetenschappers. Helemaal mee eens. We hebben het hier nota bene gehad over een fout in het IPPC rapport, en eerder heb ik ook al aangegeven dat wetenschappers ook gewoon mensen zijn die fouten kunnen maken…

@Marcel

"Voor jou kan AGW de beste verklaring zijn voor alle puzzelstukjes, maar voor diverse andere wetenschappers is het dat niet, denk aan de drie hypotheses van Pielke sr."

Ik ken die hypotheses (ik ben hydroloog; ik ken meerdere van de auteurs van het betreffende EOS artikel). Zoals je in het EOS artikel van Pielke et al kunt lezen gaan ook zij uit van de geldigheid van CO2 gestuurde AGW *plus additionele processen*. Ik citeer:

"Hypothesis 2a: […] including, but not limited to, the human input of carbon Dioxide (CO2)."

en

"hypothesis 1 is not well supported"

en

"We therefore conclude that hypothesis 2a is better supported than hypothesis 2b"

Ik heb nooit gezegd dat CO2-AGW de best denkbare verklaring is. Hij is alleen in de *bestaande* attributiestudies beter dan alternatieven als cosmic-rays. Feitelijk is er nog geen goede attributiestudie waarmee je kunt zien of Pielke's 2a beter is dan 2b. Dat is nu juist het probleem dat ze (terecht) aanstippen.

Maar in ieder geval kun je uit het aannemelijk gemaakt zijn van de relevantie van additionele first-order processen NIET concluderen dat antropogeen-co2 geen verklarende rol heeft in de gemeten klimaatstijdreeksen.

"Over attributie gesproken, erken jij dat ‘het bewijs’ voor AGW is dat modellen alleen overeenkomen met observaties van de mondiale T als de broeikasgassen flink bijdragen aan de opwarming? Want volgens mij is dat nog altijd het bewijs waar het IPCC op leunt (zie ook Nature van deze week, verschijnt morgen een interessant news feature)."

In principe wel ja. Het wetenschapsfilosofische principe waar ik van uit ga is dat het best en meest verklarende mechanisme wint. Voorlopig dan hè?

Staat dat Nature News feature al online? Op dit moment zie ik alleen een News Feature over glacier-gate.

"In dat geval hangt het bewijs dus van twee belangrijke pijlers af, hoe goed zijn de modellen en hoe goed zijn de observaties?"

Eens.

"Zoals je weet valt er op beide nog heel veel af te dingen. De global T van CRU, GISS en NCDC is echt een puinhoop en als daar echt een keer goed naar gekeken wordt door ‘onafhankelijke onderzoekers’ (dus niet Jones en Hansen, Karl etc.) dan zal blijken dat het merendeel van de trend ‘adjustment’ is."

Dat is nog maar de vraag. Ik ben het er wel mee eens dat de betrouwbaarheid van de global T (opnieuw) vastgesteld moet worden, gezien alle rumoer. Maar de argumenten die ik heb gezien waarom het niet zou deugen, daar ben ik niet direct van onder de indruk. Als je de critici mag geloven is elke aanpassing van stationdata verboden, wat natuurlijk onzin is aangezien je xyz puntdata moet omschalen naar gebiedsdata op een referentiehoogte. Je kunt dus überhaupt geen global T op basis van stationdata produceren zonder adjustments…

"Daarna gaan we kijken naar de haken en ogen in de modellen die nog huge zijn, denk aan convectie, wolkenvorming, neerslag etc."

Klopt. Maar we kunnen nu eenmaal niet anders dan met de beste modellen werken die er zijn. En aan verbetring wordt gewerkt.

"De volgende kwestie wordt dan of de modellen al de toekomst kunnen gaan voorspellen. Lucia op The Blackboard heeft laten zien dat de voorspelling sinds 2001 voorlopig helemaal mis gaat. Ok, misschien nog te kort om de modellen helemaal af te branden, maar laten we onze ogen er ook niet voor sluiten."

Aan de andere kant voorspellen modellen ook dat een kortdurende (~10jr) stabiele of lichte afkoelingsperiode, zoals we die sinds cherry-pick jaar 1998 zien, hoogstwaarschijnlijk is, ook onder AGW opwarmingstrend…

Marcel,

Naar aanleding van je reactie op Boog:

("Interessant, ben het met je opmerking over Popper wel eens, falsificatie is heel lastig in klimaatonderzoek.")

– Kan een niet falsificeerbare hypothese wetenschappelijk zijn? Of hebben we het dan simpelweg over geloof?

– Hoe wetenschappelijk is dan een hypothese die moeilijk falsificeerbaar is?

– Welke criteria voor het leveren van bewijs moet je dan hanteren voor de AGW-theorie? Zou bijvoorbeeld een model met een grote voorspellende waarde daartoe kunnen dienen? (Vergelijk het met de chemie: het periodiek systeem der elementen)

– Is het in dat geval redelijk om van de aanhangers van de AGW-theorie een model te verwachten dat de klimaatontwikkelingen accuraat voorspelt?

– Of zie je nog andere manieren voor de AGW-groep om met een overtuigend bewijs te komen?

Peter,

allemaal heel goede vragen en ik heb niet een twee, drie antwoorden.

Wetenschap is story telling, en de story die veel onderzoekers nu aannemelijk (of aantrekkelijk :)) vinden is dat het broeikasverhaal. Maar er zijn zoveel puzzelstukjes en het geheel is zo diffuus dat er vele andere verhaaltjes mogelijk zijn, denk aan 'er is negatieve feedback in het systeem' (Lindzen, Spencer), de zon is veel invloedrijker (Soon, Scafetta, Svensmark) maar ook iemand als Harry van Loon. Dan Pielke sr, het is de mens, maar door een veelvoud aan factoren, landgebruik, aersolen, roet, effect van CO2 op de biosfeer en daardoor weer op de watercyclus en bodemvocht (moet jou aanspreken Boog :)