Roet heeft een enorme potentie om ijs te smelten, maar ook de atmosfeer.

Deze week is er weer veel aandacht voor roet, een deeltje dat de laatste jaren sowieso aan een indrukwekkende opmars in de klimaatwereld bezig is. Die opmars is voor een groot deel te danken aan V. Ramanathan, een van de grondleggers van de moderne broeikastheorie, die zich in de nadagen van zijn carrière op het onderwerp roet heeft gestort. De eerste van twee artikelen die zijn verschenen is dan ook mede van zijn hand. Het persbericht legt uit dat de onderzoekers op basis van metingen boven Zuid-Korea concluderen dat roet uit fossiele brandstoffen (vooral diesel) 100 keer zo sterk zonlicht absorbeert dan roet uit biobrandstoffen (hout, mest). Een tweede artikel van Mark Jacobson stelt dat roet zo sterk bijdraagt aan opwarming dat het op de tweede plaats komt, na CO2 en nog voor methaan.

Een miljoen keer sterker

Het tweede artikel van Mark Jacobson in de Journal of Geophysical Research onderzocht het effect van roet met modellen. Jacobson keek daarbij toevallig ook naar het verschil tussen roet afkomstig van biobrandstoffen en fossiele brandstoffen. Per eenheid van gewicht is het opwarmingspotentieel van roet indrukwekkend te noemen. Elke gram roet afkomstig van fossiele brandstoffen warmt de lucht 1,1 tot 2,4 keer sterker op dan een gram CO2. Roet van biobrandstoffen is volgens Jacobson 350.000 tot 970.000 keer zo sterk als CO2.

Als gevolg daarvan komt roet volgens Jacobson op de tweede plaats terecht in het rijtje van mondiale opwarmers, achter CO2 en nog voor het sterke broeikasgas methaan. Omdat roet ook voor grote gezondheidsproblemen zorgt, met name in ontwikkelingslanden, ligt het voor de hand om roet de hoogste prioriteit te geven in klimaatbeleid. Je slaat immers twee vliegen in een klap, een afname van roet leidt tot een schonere lucht en minder gezondheidsklachten en zou tegelijkertijd voor wat afkoeling kunnen zorgen. Een heuse win-win situatie.

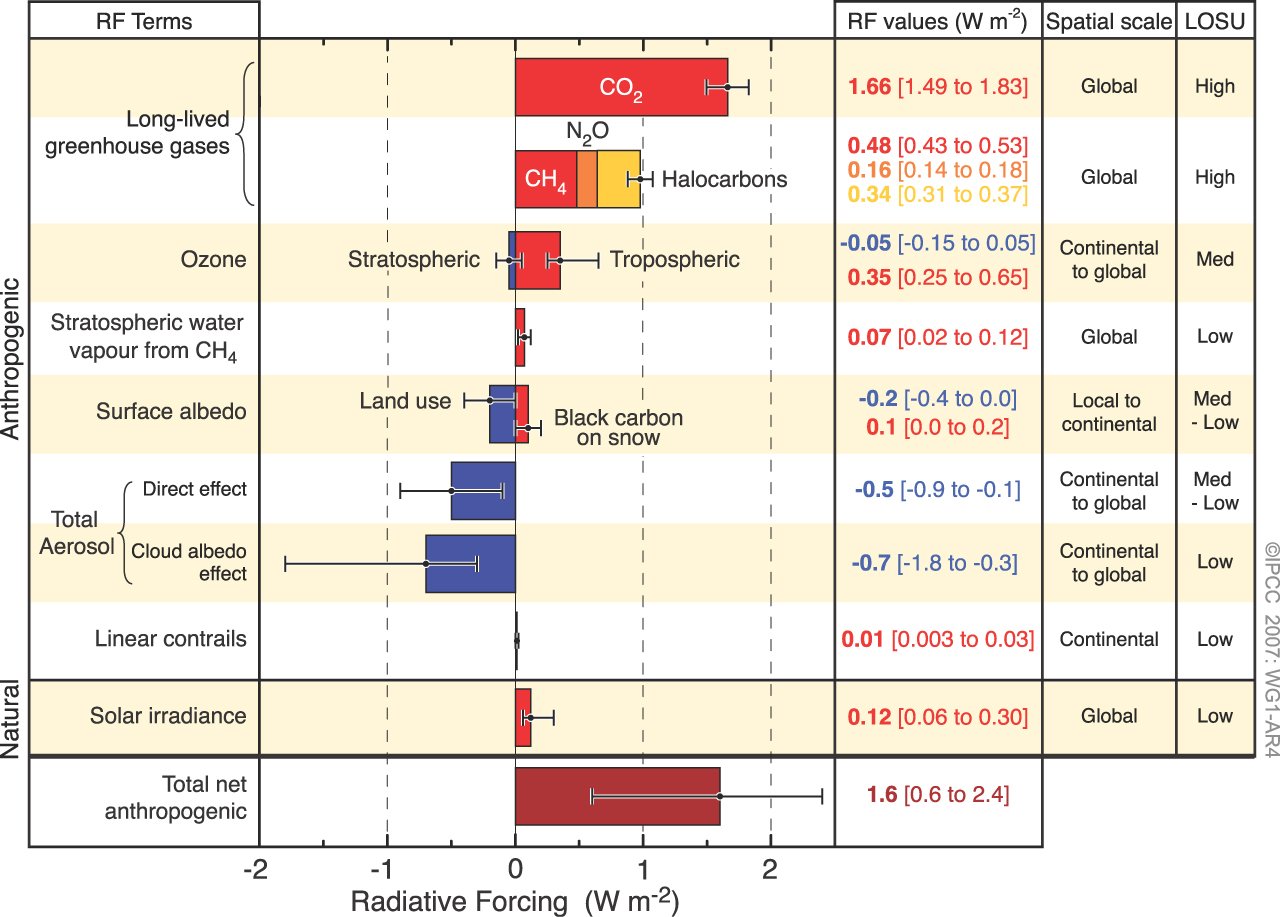

Wat vrijwel nooit aandacht krijgt in dit soort publicaties is dat een grotere rol voor in dit geval roet betekent dat het effect van CO2 kleiner zal moeten zijn dan tot nu toe gedacht. Kijk maar naar figuur SPM.2 van het laatste IPCC-rapport:

Hoeveel komt door CO2?

Roet wordt hier weliswaar vermeld, maar alleen de bijdrage van black carbon aan het smelten van sneeuw. Jacobson en ook Ramanathan (in 2008 al in een eerdere paper in Nature Geoscience) stellen dat het opwarmende effect van roet veel groter is dan hier vermeld door het IPCC. Ramanathan schat zelfs zo’n 60% van het effect van CO2. Dat betekent dat de netto stralingsforcering groter zal worden. Dit betekent dan weer dat de opwarming die al heeft plaatsgevonden verdeeld moet worden over weer een extra factor van belang, namelijk roet.

Optelsom

Wat betekent dit nu voor de broeikasdiscussie? We nemen de opwarming sinds 1975 van pakweg een halve graad Celsius, die doorgaans aan de mens wordt toegeschreven. Peer reviewed artikelen van onder andere Michaels/McKitrick, De Laat/Maurellis, Pielke sr/Klotzbach hebben meer dan aannemelijk gemaakt dat een deel van die recente opwarming veroorzaakt is door slechte kwaliteit meetstations en economische factoren. Laten we zeggen dat er 0,3 graden klimatologische opwarming overblijft.

We moeten vervolgens nog rekening houden met de Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) die in die periode in een warme fase zat. Dat is meer dan redelijk omdat er toenemend bewijs is dat de huidige stagnatie van de wereldtemperatuur mede te wijten is aan de koude fase van de PDO. Volgens de klimaatmodellen had de aarde tussen 2000 en 2010 0,2 graden moeten opwarmen, maar er was opwarming noch afkoeling. De zon ging in dezelfde periode naar een ongekend minimum, zal ook iets hebben bijgedragen, dus een voorzichtige schatting zou kunnen zijn dat de PDO 0,1 graden heeft bijgedragen aan de opwarming tussen 1975 en 2000.

Blijft er 0,2 graden over. Deze opwarming moet verdeeld worden over alle forcings die in de tabel vermeld staan met de kanttekening dus dat roet waarschijnlijk meer heeft bijgedragen. Een volgende kanttekening is bovendien dat het afkoelende effect van aerosolen, de grote blauwe balk in de tabel, waarschijnlijk veel minder koelend is dan het IPCC tot nu toe heeft gedacht, zie dit eerdere bericht op climategate.nl. Dit maakt de netto opwarmende forcering wederom groter. Zo blijft er al met al misschien maar 0,05 graden over die we direct aan CO2 kunnen toeschrijven.

Het is natuurlijk natte vingerwerk, maar, ik zou het geen speculatie willen noemen. Dit is het model dat het IPCC zelf aanhangt. Opwarmende en afkoelende factoren tegen elkaar wegstrepen, het netto eindresultaat bepaalt hoeveel de aarde zou moeten opwarmen. Als veel netto forcing relatief weinig opwarming geeft, dan is dat een indicatie dat het klimaat niet zo gevoelig is voor die forcings. Dat wijst ook eerder in de richting van negatieve feedbacks (denk aan het werk van Lindzen en Spencer) dan de behoorlijk positieve feedbacks die er in alle 21 klimaatmodellen van het IPCC zitten en kan verklaren waarom de modellen de opwarming voor de toekomst vooralsnog overschatten.

Voor de volledigheid hieronder het persbericht over het artikel van Jacobson, inclusief een interviewtje van drie minuten met Jacobson.

Ordinary soot key to saving Arctic sea ice

AGU Release No. 10–20

27 July 2010

For Immediate Release

WASHINGTON—The quickest, best way to slow the rapid melting of Arctic sea ice is to reduce soot emissions from the burning of fossil fuel, wood and dung, according to a new study.

The study shows that soot is second only to carbon dioxide in contributing to global warming. But, climate models to date have mischaracterized the effects of soot in the atmosphere, said its author Mark Z. Jacobson of Stanford University in Stanford, California. Because of that, soot’s contribution to global warming has been ignored completely in national and international global warming policy legislation, he said.

“Controlling soot may be the only method of significantly slowing Arctic warming within the next two decades,” said Jacobson, director of Stanford’s Atmosphere/Energy Program. “We have to start taking its effects into account in planning our mitigation efforts and the sooner we start making changes, the better.”

The study will be published this week in Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres). Jacobson used a computer model of global climate, air pollution and weather that he developed over the last 20 years and updated to include additional atmospheric processes to analyze how soot can heat clouds, snow and ice.

Soot — black and brown particles that absorb solar radiation — comes from two types of sources: fossil fuels such as diesel, coal, gasoline, jet fuel; and solid biofuels such as wood, manure, dung, and other solid biomass used for home heating and cooking around the world.

Jacobson found that the combination of the two types of soot is the second-leading cause of global warming after carbon dioxide. That ranks the effects of soot ahead of methane, an important greenhouse gas. He also found that soot emissions kill over 1.5 million people prematurely worldwide each year, and afflicts millions more with respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, and asthma, mostly in the developing world where biofuels are used for home heating and cooking.

Jacobson found that eliminating soot produced by the burning of fossil fuel and solid biofuel could reduce warming above parts of the Arctic Circle in the next fifteen years by up to 1.7 degrees Celsius (3 degrees Fahrenheit). For perspective, net warming in the Arctic has been at least 2.5 degrees Celsius (4.5 degrees Fahrenheit) over the last century and is expected to warm significantly more in the future if nothing is done.

Soot lingers in the atmosphere for only a few weeks before being washed out, so a reduction in soot output would start slowing the pace of global warming almost immediately. Greenhouse gases, in contrast, typically persist in the atmosphere for decades — some up to a century or more — creating a considerable time lag between when emissions are cut and when the results become apparent.

The most immediate, effective and low-cost way to reduce soot emissions is to put particle traps on vehicles, diesel trucks, buses, and construction equipment. Particle traps filter out soot particles from exhaust fumes. Soot could be further reduced by converting vehicles to run on clean, renewable electric power.

Jacobson found that although fossil fuel soot contributed more to global warming, biofuel-derived soot caused about eight times the number of deaths. Providing electricity to rural developing areas, thereby reducing usage of solid biofuels for home heating and cooking, would have major health benefits, he said. Soot from fossil fuels contains more black carbon than soot produced by burning biofuels, which is why there is a difference in warming impact.

Black carbon is highly efficient at absorbing solar radiation in the atmosphere, just like a black shirt on a sunny day. Black carbon converts sunlight to heat and radiates it back to the air around it. This is different from greenhouse gases, which primarily trap heat that rises from the Earth’s surface. Black carbon can also absorb light reflecting from the surface, which helps make it such a potent warming agent.

Black carbon has an especially potent warming effect over the Arctic. When black carbon is present in the air over snow or ice, sunlight can hit the black carbon on its way towards Earth, and also hit it as light reflects off the ice and heads back towards space. Black carbon also lands on the snow, darkening the surface and enhancing melting.

“There is a big concern that if the Arctic melts, it will be a tipping point for the Earth’s climate because the reflective sea ice will be replaced by a much darker, heat absorbing, ocean below,” said Jacobson. “Once the sea ice is gone, it is really hard to regenerate because there is not an efficient mechanism to cool the ocean down in the short term.”

Jacobson is a senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment. This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, NASA, the NASA high-end computing program, and the National Science Foundation.

Over roet in het eten.

“Je slaat immers twee vliegen in een klap, een afname van roet leidt tot een schonere lucht en minder gezondheidsklachten en zou tegelijkertijd voor wat afkoeling kunnen zorgen. Een heuse win-win situatie.”

Wat ook vrijwel nooit aandacht krijgt bij dit soort bijzinnen is dat het overgrote deel van de medische klachten als gevolg van luchtverontreiniging betrekking heeft op die delen van de derde wereld waar men zijn potje kookt op open vuur. In huis wel te verstaan. In Afrika bij voorbeeld zijn de dieseldampen buiten voornamelijk afkomstig van de vierwiel aangedreven Saheltractoren van de verzamelde hulporganisaties. Vanuit de airconditioned cabine heb je er allemaal niet zo’n erg in blijkbaar.

Maar weer eens wordt hier het bewijs geleverd dat de klimaatwetenschappen nog maar in de kinderschoenen staan. De vraag is nog steeds of de aarde wel opwarmt of niet (de laatste 10/11 jaar in ieder geval niet), laat staan of een eventuele opwarming door de mens wordt veroorzaakt d.m.v. Co-2.Nu is roet weer een van de boosdoeners en wordt inderdaad terecht opgemerkt dat de rol van Co-2 kennelijk veel minder groot is dan sommigen ons willen doen geloven. De wetenschap is zo langzamerhand verworden tot een verlengstuk van de politiek. Hoe meer subsidies de wetenschap ontvangt des te sterker laat men het geluid doorklinken van de (vaak onwetende) politiek. En de politiek zich maar het hoofd buigen hoe te bezuinigen, terwijl de oplossing voor het oprapen ligt.

Marcel,

De grote propaganda coupvan deze week was het angstaanjagende bericht over de teruglopende hoeveelheid plankton in onze oceanen.

Soot/roet is een "old cow".

http://pgosselin.wordpress.com/2010/07/29/foodcha…

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2010/07/30/now-its-phy…

Roet en fijnstof als gevolg van het verbranden van fossiele of bio-brandstof.

De oliemaatschappijen zijn zeer wel in staat om daar ingrijpend iets aan te doen.

Alleen…ze moeten een stof toevoegen die de verbranding verbetert waardoor de brandstof aanzienlijk beter en vollediger verbrandt hetgeen resulteert in extreem minder roet, fijnstof en ook beduidend minder CO2.

Echter, het beter verbranden van brandstof levert een minderverbruik op, en als de oliemaatschappijen dus maatregelen zouden nemen om roet,fijnstof en co2 aan te pakken dan zorgen ze ook direct voor minder omzet van hun brandstoffen.

Verreweg de grootste vervuiling komt van zware diesel die bijvoorbeeld wordt gebruikt in schepen.

Wat moeten oliemaatschappijen doen om deze brandstoffen beter te laten verbranden?

Zorgen dat de uiteindelijke verneveling van ingespoten brandstof zo optimaal mogelijk gebeurt. De moleculen in diesel hebben nogal de neiging samen te klonteren, wat een optimale verbranding tegenwerkt.

Het toevoegen van een stof als aceton (slechts 2 tot 5 promille) zorgt er direct voor dat diesel beter vernevelt, beter en schoner verbrandt, en ja, het zorgt er ook voor dat een minderverbruik van 20-30% wordt gerealiseerd.

De oliemaatschappijen zijn absoluut niet voornemens om dit te realiseren, zij zien het lijk al drijven, 20-30% omzetvermindering!!!

Individuele gebruikers (verbruikers) van diesel kunnen natuurlijk zelf aceton aan hun brandstof toevoegen.

Dat geeft direct mooie resultaten zonder dat daar ook maar één nadeel aan zit.

Zelfs 100% aceton tast de leidingen in het brandstofsysteem op geen enkele manier aan, laat staan een verdunning van 200-500 keer.

Het totale verbruik van zware diesel veroorzaakt meer vervuiling dan het totale verbruik van normale diesel.

Het toevoegen van aceton reduceert die vervuiling met minimaal 80%

Wat ik nog aan mijn vorige reactie kan toevoegen is dat hetzelfde wat voor diesel geldt ook voor benzine en kerosine geldt.

Elke verbrandingsmotor heeft zo zijn eigen optimale "punt", zodat je door uittesten moet uitvinden wat het optimale bijvoegingspercentage is. Dit ligt echter ALTIJD tussen de 1,5 en 5 promille.

Ook een benzinemotor zal veel schoner en zuiniger verbranden als er aceton is toegevoegd.

Jammer is dat het tegenwoordig verplicht is om ethanol (4%) aan benzine toe te voegen onder het mom van milieuvriendelijkheid.

Met ethanol wordt echter het tegenovergestelde bereikt.

Ethanol is een vorm van alcohol, en alcohol trekt water aan.

Alcohol in benzine zorgt voor een slechtere verbranding en voor meer vervuiling. (Grofweg een 10% toename)

Aceton in benzine beperkt deze negatieve werking van ethanol in benzine voor een groot deel.

Wat is eigenlijk het punt? Als het aantoonbaar juist is wat u zegt kan de brandstofprijs toch navenant omhoog (en de accijns natuurlijk een tikje omlaag). Einde olievoorraad weer verder uit zicht dus nog langer de tijd om over prachtige alternatieven na te denken. Alleen maar voordelen dus. Iedereen blij. Nou ja iedereen? Niet de milieubeweging, want die zitten niet zo te wachten op oplossingen voor problemen waarmee zij hun brood smeren.

Vraag: heeft u e.e.a. zelf al eens geprobeerd? En wat zijn de resultaten?

P.s. TSI: Mik voor het terugvliegen even een krat nagellakremover in de 737

@René Brioul:

De oliemaatschappijen hebben weinig te klagen hoor.

In de loop van de tijd hebben "milieumaatregelen" ervoor gezorgd dat motoren veel meer gebruiken dan noodzakelijk is.

Je noemde er zelf al 1, en wel de toevoeging van biobrandstof. Dat spul heeft zowieso een mindere verbrandingswaarde + dat het ook nog eens doorzet naar het verbrandingsbeeld van het minerale gedeelte. Zo kun je ongeveer rekenen op +10% hoger verbruik wanneer je 5% bio toevoegt.

Oh jah, die biobrandstof verkopen ze ook nog veel te duur + dat er subsidie op zit..

Vette winst voor de olieboeren.

Maar dan zijn we er nog niet.

Neem nou een EGR-klep. Om bepaalde emissienormen te halen gebruikt men een EGR om uitlaatgassen aan de inlaatlucht toe te voegen.

Dus men ontwikkelt super-luchtfilters die zo weinig mogelijk weerstand hebben, zet er turbo's op, de constructeurs maken het inlaattraject zo vloeiend mogelijk etc. Dat alles om maar zo veel mogelijk zuurstof in die motor te krijgen.

En vervolgens gaat men uitlaatgassen aan die lucht toevoegen…

Afgezien dat je rendement dan met sprongen zakt, vervuilt ook het inlaatgedeelte van de motor. Als resultaat van dit alles krijg je een waardeloos lopende motor die nogal wat brandstof extra moet slurpen om aan zijn vermogen te komen.

Dus afblinden die klep. Geen APK-meetapparaat die het merkt.

Het roetfilter is ook zo'n lekker brandstofslurpertje.

Niet alleen vanwege de hogere weerstand in de uitlaat, maar ook omdat je brandstof in de uitlaat moet spuiten om 'm schoon te branden. Dit veroorzaakt die enorme roetwolk die je nog wel eens achter auto's ziet verschijnen wanneer ze op de snelweg rijden.

Of die wolk nou zo goed is voor het milieu is nog maar de vraag natuurlijk, maar wie de winst pakt is duidelijk.

Of wat dacht je van de CCR2- motoren?

Volgens de groene brigade hartstikke goed voor het milieu.

Volgens de mensen die er mee draaien hartstikke goed voor de oliemaatschappijen omdat ze 12,5% MEER gebruiken dan een ouderwetse motor. http://www.schuttevaer.nl/nieuws/techniek/nid1276…

Dit komt doordat men, om maar "schone" uitlaatgassen te krijgen, te laat nog een hoeveelheid brandstof inspuit.

Die te laat ingespoten brandstof levert 0,0 rendement aan het vermogen, dus dikke winst voor de olieboer.

Zo zijn er nog wel een paar grapjes die een hoger verbruik geven dan noodzakelijk, maar ik vind het wel weer goed voor deze zondag. ;~)

Als ik een zeer conservatieve schatting mag maken kan het verbruik van de meeste moderne diesels op z'n sloffen met 25% naar beneden.

Maar jah, meer brandstof verstoken is blijkbaar beter voor het milieu he?

En dan zijn er nog mensen die niets willen weten van de liefde tussen big oil en big environment.

@woedende kok:

Of ik het zelf heb geprobeerd? Jazeker, ik voeg al jaren aceton toe aan zowel diesel als benzine.

De diesel (een camper die normaliter 1:8 liep loopt nu 1:10,5) loopt ook hoorbaar beter en veel schoner. Bij de jaarlijkse apk roetmeting wordt herhaaldelijk op het uitleesapparaat getikt omdat er onwaarschijnlijke lage waarden worden uitgelezen.

De benzine auto is een personenauto, een Renault Laguna die normaliter een gemiddeld verbruik heeft van 1:10,5 en nu gemiddeld 1:13,7 loopt.

Nagellakremover zou ik niet gebruiken tenzij het 100% zuivere aceton is. Bovendien is die nagellak remover en aceton gekocht bij drogisterijen veel te duur.

@ Leo Bokkum:

Ik ben het helemaal met je eens. De techniek kan vele malen beter dan dat het nu is, maar het is natuurlijk van de zotte dat de brandstof die verstookt moet worden verre van optimaal is en zelfs goede resultaten poogt te blokkeren.

Ik geloof ook niet (meer) dat de politiek geinteresseerd is in dit soort oplossingen (ervaring) maar dat het alleen maar gaat om vormen van belastingheffing en overige afdwingmethodieken zoals verplichte (roet)filters en andere ongein.

Zijn er dames/heren van het PBL, ECN, Energieraad, VROM, VWS, VenW, EZ, OCW, IPCC, GL, enz. die willen reageren op het door René Brioul gestelde?

Ook Vendrik mag reageren.

Jongens, kijk eens even hoe de brandende toendra een mooi laagje roet over het Arctische zeeijs uitstrooit.

Rene, hoe doe ik dat aceton-verhaal in m'n LPG auto?

(Ik kan wel een manier bedenken, maar of dat veilig is weet ik niet.

een paar druppels aceton in de vul-opening druppelen voordat je met de bajonet-koppeling de lading LPG er in perst.) Heeft dat zin?

@LeClimatique:

Helaas, voor LPG gaat het verhaal niet op.

Alleen voor een vloeibare brandstof waarmee je de aceton kunt mengen.

@Boels069:

Ik heb ze allemaal meerdere keren aangeschreven.

NIEMAND is in dit soort (te makkelijke?) oplossingen geinteresseerd.

Raar maar waar.

Voor overige informatie kan je kijken op de website die "onder mijn naam" zit. Pagina Brandstof besparen…

Zelfs de locale busmaatschappij in Nijmegen wilde er niet aan omdat ze van hun brandstofleverancier geen toestemming kregen…